Fundies Love Pomos

A follow up on my last post and the helpful discussion afterward....

Mo and PoMo

Post-modernism is pretty difficult to pin down since so far nobody seems to agree on what it means.

My take? Post-modernism is more a mood than a movement. It's a point of view rather than a program.

Modernism, by contrast, is relatively clean and clear.

The founders of modernism during the Enlightenment rejected the primary influence of organized religion and focused on secular human social progress. They believed intensely in the potential of human society and human reason. The scientific method was their tool. Liberal (in the older, less perjorative sense of that word) democracy and free market economies were their practical program.

Post-modernism, if it even deserves such an historically significant title at this point, seems to be mostly a reaction against the excesses and arrogances of modernism.

One of you commented that you hoped post-moderns were more than just "anti" in their "post-ness." From my point of view pomo is mostly anti at this point and hasn't added a whole lot yet of lasting value beyond furnishing a very important critique of the modernist project. That critique is potentially life giving and important. I'm not sure, though, that pomo has gotten much beyond the criticism to suggest a better alternative.

If modernism is the machine, raging against it only gets you so far.

But even among critics of modernism the pomos are a little late to the game. Religious communities--particularly the more anarchical and honest spiritual groups that are suspicious of organized religion along with the modernists--have been making those critiques of modernism for centuries.

And various "romantic" movements since the Industrial Revolution have taken the fight to the modernists too. From the late 18th century and early 19th century "Frankenstein" generation to the 60's social revolution lots of people understood the destructive downside to modernism.

Since the recognizable current form of pomo is only a few decades old, I'm sympathetic. Moods take time to transform into movements and programs that can actually make a long term difference.

What's the pomo mood?

Seems like eclecticism is the touchstone of the pomo take. Certainties look highly questionable and the odds are that something creative and life giving will probably come out of mixing and matching and asking hard questions.

If you think about it, that pomo mood conserves an important part of modernism.

The scientific method is the beating heart of modernism. Its all about scepticism and challenging certainties with facts, or in other words, humility in the face of experience.

Personally, I think the scientific community and the track record of the scientific method have contributed more to the immediate and practical well being of people around the world than anything else I can think of, so it makes sense that the pomo mood would make room for the heart of modernism. It would be crazy not to.

And I don't hear or read of many pomos who want to roll back the modernist program of liberal democracies and economies. Lots of people are angry about the abuses of the powerful in those systems of politics and economics, but I don't see anything in the practical expression of pomo--if there is such a thing--that seems like a real challenge to those approaches.

So how is pomo really different than modernism since most people who identify with it buy into the heart of the modernist agenda? You could actually argue that American pomos are ultra consumers and materialists and are more committed to the democratic and liberal political and social agendas of modernism than any generation before them. And I include "religious" pomos among them.

One clear difference seems to be the pomo approach to words and meaning. Moderns believe words have understandable and largely objective meanings which can be discerned with hard work and empathy. Ideological pomos tend not to.

But even here I'm not sure that difference makes a major difference on a day to day level. I doubt that many people who identify with pomo really understand--or accept--the intellectual heart of the whole thing. In other words, even folks who take words and meanings at face value can still view themselves as pomo.

I think there is another, more immediately practical difference that's important for the topic at hand.

Up and Down of PoMo

It gets back to the eclecticism of pomo.

Pomos seem to want to have both science and myths. Reason and what some people consider irrationality.

That committment to synergy and an openess to the "irrational" and mythical and religious may be the greatest strength of pomo.

But when you open that particular front door you never know who will walk in.

That may be the weakness of the current cultural mood. The New Testament talks about a "spirit of the age." I think that's what pomo is among people between 20 and 35 in the US and Europe.

During the golden age of modernist influence (1930--1975?)in the US, very few self-respecting people with an education would have supported the idea of teaching religious myths in a public school science class.

Now 60-65% of the population, including lots of educated people who think Genesis is sort of silly, are open to that kind of thing.

Maybe that shift is just "American pragmatism," but I think something deeper is going on.

Post-modernism has been the best thing to come along in about a century for evangelicals and fundamentalists. During the reign of modernism serious religious types lived in a tent on the front lawn of politics and the university. Pomos have opened the front door to them in a new way.

The Atlantic Monthly published a remarkable article last year about the increasingly post-modern spirit of Fuller Seminary, once a center of traditional conservative Christian thought and practice. Many of the faculty and students they interviewed were explicitly grateful for post-modern attitudes and how that new cultural current had "given us an important place at the cultural table."

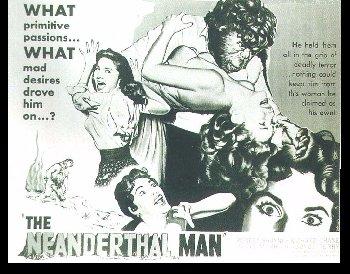

Some secular pomos like to believe that current American Christian fundamentalists are mostly pre-modern Neanderthals. But they aren't. They reject the idea of evolution because they believe it contradicts basic biblical teaching, but in most respects they accept the central importance of science and (especially) technology and are committed and grateful consumers of the bounties of modernism.

In short, you could argue that they are simply eclectic post-modernists who like a generous blend of fact and myth. Even if that extends to the local public school science class. They just take their myths a little more seriously than some and have a deeper distrust of what they perceive to be the scientific establishment.

Unlikely Partners?

For secular and even religiously oriented pomos with wider scientific sympathies, the rise of fundamentalist and conservative Christian influence might beg the question, "guess who's coming to dinner?" The "big house" of pomo may have some pretty unlikely room-mates living together under the same roof.

Obviously, I'm disturbed that any school district would seriously consider teaching religious myths in classes dedicated to scientific instruction, so please don't take what I'm writing as an endorsement of that idea.

I'm just interested in the seemingly unlikely intersection of fundamentalism and post-modernism and how that might contribute to a gathering cultural consensus in favor of relaxing the traditional modernist dividing line between science and religious myth in the classroom.

7 Comments:

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

Yes, I think you're right that an almost "interpersonal" relativism is more what's going on than a clear ideology. Folks want to validate and be validated, so to speak. So that leads, as you say, to some great things like greater racial rec and diversity in various communities, but also to some of the downsides folks have mentioned.

As someone who identifies pretty heavily with postmodernism, perhaps naively, I feel as though I can defend post-modernism as an ideology, even a program, though the ideas can render their articulation or definition problematic. For example deconstruction a la Derrida, in "de la Grammatologie", is usually interpreted as self-annihilating, in arguing that words are meaningless, therefore anything in the book is meaningless. But that ignores the obvious fact that he did communicate an idea through words, despite his awareness that each one of those words is subject to an analysis which can strip it of any meaning. This is similar to something I mentioned in a post on my blog, that on a "quantum mechanics" level - word by word, or letter by letter, the "Newtonian" generalizations of meaning don't hold, but in the scope of the general work, Derrida does express his point. I am sure you are now thinking, "Why is he legitimating postmodernism with science?" which is to say why am I, as a pomo, legitimating the discourse of science? It is inherently self-legitimating, because it is a "language game" made up of only denotative phrases which would make it the most sure form of knowledge, except that there is no way to legitimate the language game, the discourse, except from narrative knowledge (or some other non-denotative phrase). And where do we look for this legitimating narrative? Genesis maybe? Or even the example of the regenerating work of the Holy Spirit? Modern science has formulated it's developments as building on one another in a sequential fashion. Postmodern science is undermining legitimation by performativity (efficiency of what can be done with it for the amount put into it) by retheorizing the way science itself develops: science does not develop in a progressive fashion and towards a unified knowledge, but in a discontinuous and paradoxical manner, undermining previous paradigms by the development of new ones. This is what Jean-Francois Lyotard, the author of the first benchmark work defining postmodernism, calls legitimation by paralogy (para defined as beyond, beside; logos defined as the universal and immutable faculty of reason). He suggests that science may be undergoing a paradigm shift from deterministic performativity to the paralogy of instabilities. While of course I think there is an ultimate culmination of all knowledge in God, we don't see how we are working toward that really - it is beyond our scope. Just as scientific discovery can be portrayed as building upon one discovery after another from the enlightenment to some grand unified theory yet to come, it also can be seen as a discontinuous series of contradicting theories, which are completely new from their predecessors. The first, if describing a Christian's life could describe a person's steady growth in Christ, whereas the latter might be parallel to a person's complete transformation by the Holy Spirit. Though from a natural point of view, the former may seem more descriptive, and even more useful in terms of encouraging a brother or sister to be more Christ-like. It is only the para-logical explanation that can really explain everything. I think Post-modernism is an ideology which accepts multiple/parallel explanations of the same phenomena as important, (i.e. it embraces everything and everyone) while trying to give voice or lend credence to those which are less practical (performatively legitimable), because these have a potential to more comprehensively address the "outliers." I will try to discuss these ideas further on my blog, filling in some of the gaps, or terms/authors with whom I assumed some familiarity.

Great stuff, ahomily. I look forward to reading your further explanation.

I agree with your more detailed description of the ideas underneath post-modernism, though as I mentioned, I've run across very few pomos that are conversant with those ideas. That's part of what makes discussing it with people difficult.

At the risk of oversimplifying, you seem to identify pomo primarily by means of 1) hermeneutics and 2) worldview. If that is what you're doing, I agree those two categories are the heart of what makes pomo different from modernism from an ideological point of view.

Briefly, I do think the inherently delegitimizing hermeneutics of pomo which you mention (exemplified by Derrida)are a major problem. That's one of the primary obstacles that's kept me from embracing pomo intellectually.

On the other hand, I've found it easy to embrace much of pomo thinking on worldview. Way back when I was a college student I was very struck by James Sire's "The Universe Next Door." Sire is an explicitly Christian author who wrote what can only be called a "world view" catalogue. Though Sire wasn't and isn't pomo, he outlined very elegantly a variety of discontinuous world views, including modernism, and compared them. His main point was that people tend to think in terms of relatively self-contained and self-referential "world views."

That insight seems to me to be one of the most important contributions of pomo thought. Thomas Kuhn's well known "The Structure of Scientific Revolutions" took that kind of worldview thinking and applied it to the modernist scientific project. Basically, he argued that science proceeds through a succession of different "scientific world views" which don't proceed one after another "logically." Getting from one of those world views (Ptolmaic cosmology to Newtonian physics, for example) is really more of a "conversion" experience from one set of assumptions to a wholly different set than it is a logical, careful progression from ignorance to knowledge (as modernism would describe it.

I mention those two books because they may be more accessable to folks reading along. Derrida and some of the other pomo thinkers are--in my opinion--relatively poor writers with a genius for making their thinking obtuse and over-complicated.

I like this emphasis on parallel explanations and world views, and I think it helps explain the "openess" of pop pomo and some of the breakthroughs in racial reconciliation and cultural diversity among younger pomos. It also tends to encourage patience and a willingness to examine a variety of "ways of knowing and experiencing" that has never characterized modernism. That, as you say, allows for groups that aren't "performatively legitimate" by the standards of modernistic science a place at the table. So, for example, where modernism has never been open to take seriously the claims of indigenous, non-western medicine, pomos tend to be far more open to do so.

This pomo worldview analysis runs into problems practically, however, when you ask how do you legitimatly choose between alternate worldviews, and also, on what basis does a person or society 'convert' from one worldview to a new one.

Modernism's strength is that it has a very clear and compelling way to answer that question. Basically, in my view, modernists argue that we should make those choices or undergo such a conversion on the basis of whether a world view conforms well to 'facts' as demonstrated by the rigorous scientific method (which every scientist, whether pomo or not uses)and whether it demonstrably contributes to human political freedom (as defined by democracy)and human economic freedom (normally defined as some version of "free markets"). Or another way of saying that is a worldview has to stand up to the pragmatic test of "advancing human well being" as defined by modernism. Modernists tend to assume that everyone, everywhere ultimately values economic and physical well being as well as "freedom" and claim to measure worldviews on the basis of how well they contribute to those values.

While pomos may see that set of standards as naive and destructively narrow, I--and a lot of people--aren't sure pomo thinkers have made a convincing case for a practical alternative. That leads a lot of folks to view pomo--in the end--as hopelessly relativistic and impractical over the long run. Whether that's a fair critique or not, I think it's what keeps people from buying in, even if they identify with pop pomo from a cultural point of view.

Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,

But to be young was very heaven!

William Wordsworth

1805

I think I am a pre-modern. Give me truth, goodness, and beauty. And I'll take Wordsworth over both Mo and PoMo any day, thanks.

these words stuck out to me: "the traditional modernist dividing line between science and religious myth in the classroom."

This is something I've been thinking about lately: the dualistic conception of the sacred and the secular, or the spiritual and material. I suppose modernism needed this distinction to keep intellectual endeavors safe from religious dogma (and frankly I don't blame it much). But it's a false distinction- things don't always nicely separate out this way, and the spiritual and material are really all mixed up with each other. The various critiques of modernism have recognized this- you can see it in things like alternative medicine, anything labeled "holistic", etc.

I think this is what science is going to have to confront eventually- the possibility that the dividing line is somewhat blurry.

Post a Comment

<< Home